- Home

- Michael Gruber

Tropic of Night jp-1 Page 4

Tropic of Night jp-1 Read online

Page 4

“Been and gone. Where were you?”

“It’s my regular day off, Cletis. Monday? Yours too, I thought. I was going to my mom’s. Why did we catch this thing?”

“I was hanging around and picked up the phone,” said Barlow. Paz grunted. He knew that Cletis Barlow refused point-blank to do servile labor on Sundays, so he often filled in the hours he would have been docked during what would otherwise have been his regular day off. Paz asked, “What did the M.E. say? Who was it, by the way?”

“Echiverra. He figures she’s been dead a couple of days. This is Deandra Wallace. She was supposed to go over her momma’s house this morning. Her brother come by to see her when she didn’t show or answer her phone. And he found her like this. They were going to go shopping. For the baby.”

“Uh-huh,” said Paz, and moved closer to the bed. The remains were those of a young woman, perhaps twenty years old, with smooth chocolate skin. She was nude, lying on her back, arms at her sides, legs extended. There was a gold bracelet on one ankle and a gold chain around her neck, with a tiny golden cross on it. Her breasts were solid, round, and swollen. Her hands were encased in the usual plastic bags, in the event that she had touched her killer in some evidentiary fashion. When murdered she had been in the most advanced state of pregnancy. The flowered sheet on which she lay was red-black with blood and there was a pool of solidified blood on the floor. Paz was careful not to step in it.

“There’s no baby,” said Paz.

“No. The baby’s in the sink in the kitchen. Take a look.”

Paz did. Barlow heard him say, “Ay, mierditas! Ay, mierda! Ay, Dios mio, condenando, ay, chingada!” which, as he understood no Spanish, meant nothing to him. What Paz said when he came back was, “My goodness, what a terrible thing!” When you worked with Cletis Barlow, you did not use the name of the Lord in vain, at least not in the official language of the state of Florida, nor utter any foul speech. Cletis would not work with anyone who did not conform to his standards, and Jimmy Paz could not afford to annoy the only detective in the homicide unit who did not actively dislike him. Paz didn’t actually know how Cletis felt about him personally, although coming as he did from five generations of the most viciously racist people in the nation, one might assume that his very first choice of a partner would not have been a black Cuban. On the other hand, no one had ever heard Barlow use a racial epithet, something that made him fairly unusual in the Miami PD.

“Uh-huh, terrible,” Cletis agreed. “You know, you read about abominations in the Bible, but Satan is usually more roundabout in his works, these days.” Cletis mentioned the name casually, as if the Prince of Darkness were a suspect now hanging out in some local pool hall.

“You think it’s a ritual killing?”

“Well, let’s see now. No signs of forced entry. No one heard anyone holler the night we think she died, which was Saturday, or not that we heard about yet, although we’ll check some more. Then there’s the body. Look at that girl. What do you see? I mean besides what they did to her.”

Paz looked. “She looks like she’s sleeping. I don’t see any abrasions on her wrists or ankles …”

“There ain’t any. I checked. And the doc said she was alive when the cutting started. So …” Barlow paused and waited.

“She knew the people. She let them in. They drugged her unconscious. And then they cut her. Je … um, gosh, what in the world did she think was going to happen to her?”

“Well, we’ll just have to ask the boys who done it when we find them. Oh, yeah, another thing. What do you make of this here?”

Barlow took a plastic evidence bag out of his pocket and handed it to Paz.

It contained a pear-shaped, woody thing an inch or so across, like the thick shell of some nut or fruit, dark and shiny as a piano on the convex surface, dull and rough on the concave side, which bore a straight ridge down its center. Paz saw that two tiny holes had been drilled through either end.

“Looks kind of like a piece of a nutshell, drilled. Part of some necklace?”

They heard steps and a metallic rattle and the two guys from the morgue came in with their gurney.

“Holy fucking shit!” said the lead man when he saw what was on the bed.

“Watch your mouth, son!” said Barlow. “Have some respect for the dead.”

The ambo man, who was relatively new on the job, was about to come back with some smart remark when he wisely took in the expression on Barlow’s face and the expression on his own partner’s and decided to keep his mouth shut and get on with the job.

As he watched them place the remains of Deandra Wallace into a black plastic body bag, Paz reflected, not for the first time, that humor and cheerful obscenity were what made it possible for normal people to endure daily exposure to horror. That Cletis Barlow did not so indulge demonstrated that he was not a normal person, which Paz knew already, but neither did he seem to have any trouble bearing up. Paz liked figuring people out and had found that most of them were as simple as wind-up toys. The major exceptions to this in his experience were his mother and Cletis Barlow. Another thing that kept Paz willingly at his side.

“There’s another one,” said Barlow. “A baby. In the kitchen.” The morgue guys looked startled. The younger one went into the kitchen. There was silence, and the sound of slamming cabinet doors. He came out holding a white kitchen trash bag with a dark bulge at the bottom.

“No,” said Barlow. “Get a body bag.”

“A bod … for Christ’s sake, it’s a fu … it’s a fetus,” said the ambo man.

“It’s a child and it’s the image of God,” said Barlow. “It goes out of here in a body bag like a human being, not like some piece of garbage.”

The older ambo man said, “Eddie, do like the man says. Go down to the bus and get another bag.”

The two detectives waited in silence until the dead were removed from the apartment. They left the bedroom. Paz pointed to the wall. “There’s a picture missing.”

Barlow looked. “Uh-huh. And somebody went to some trouble to draw our attention to it. We’ll ask the family about it.”

“We know who the father is?”

“They will,” said Barlow.

Outside the building, the crowd had dispersed somewhat, or rather had moved across the street to where a couple of television vans had parked, and its younger members were posing for the cameras. Paz and Barlow walked down the street away from this. A PI officer would supply vague semifalsehoods for the twenty seconds of coverage that Deandra Wallace’s death would get on the local news that night, absent some more spectacular carnage involving whiter people.

A middle-aged, brass-haired, leathery woman in a nice grass-green cotton suit stepped out from between two parked cars and stood in their way.

“What’s up, guys? I hear it’s bad.” Doris Taylor had been the crime reporter for the Miami Herald since shortly after the invention of movable type, and she was good at it, which meant that Barlow ignored her and Paz cultivated her. Paz was a modern cop and understood publicity and what it could do for one’s career, while Barlow thought that reporters and the people who read them were ghouls and unclean spirits. It was an area where the two men had agreed to disagree. Barlow stepped around Taylor without a word, as if she were a dog dropping, while Paz smiled, paused, said, “Call me,” in a low voice, and moved on. Taylor flashed a grin at Paz, flipped a bird at Barlow’s retreating back, and walked back to the murder scene to gather color.

At the next corner, Raymond Wallace, brother to the deceased, was waiting in a patrol car with a uniformed officer. Paz recognized him from the graduation picture in the apartment. He was in the backseat with his head resting against the rear deck, looking stunned. The rear door of the car was open for air, and to demonstrate that the young man was not a prisoner. Like many of the people associated with the morning’s activities, he had thrown up, and his brown skin had an unhealthy gray cast to it. Barlow stuck his head in the window. “Mr. Wallace, we’re going to head back to the

station now so you can make your statement.” Raymond Wallace sighed and slid from the car. Paz noticed that his eyes were reddened and there was a splash of yellow puke on the toe of one of his white AJ’s.

“Can I call my mother?” Wallace asked.

“You need to let us do that, sir,” said Barlow.

“Why? She gonna be worried sick if I don’t call and say why I’m not back yet.”

They arrived at Paz’s car. Barlow said, “The reason is that when there’s a homicide it’s important that the police are the first people to tell the family about it. Sometimes we learn important things from their reaction.”

“You think my momma connected up with …”

“No, of course we don’t, sir, but we have to do everything according to the book. And I’d like to say now, sir, how sorry I am about your loss.”

He meant it, too, thought Paz. He feels for these people, for all of them, the bad guys and the victims both, and yet it doesn’t reduce his heart to slag and pus. Paz himself did not let himself feel anything but the coldest and most refined anger.

They traveled down Second Avenue in silence to Fifth, to the police station, a newish six-story dough-colored concrete fortification. In one of the interview rooms in the homicide unit’s fifth-floor office Raymond Wallace told his story. He lived with his mother in Opa-Locka, northwest of the city, in their own house. He’d taken his mother’s car to pick up his sister. They were going to go to a mall to buy baby things. Here he broke down. Barlow let him recover himself. Paz asked him about the missing picture and got a blank stare.

Barlow changed the subject to the family. There was just him and his sister. His father had been an air force sergeant, dead five years. His mother lived on the pension. He was a student at Miami-Dade. His sister had wanted to be a hairdresser and was studying for her license. The father of the baby was Julius Youghans, an older man, resident in Overtown. Youghans had a pickup truck and did light hauling and odd jobs. No, his mother had not approved of the relationship, but only because Youghans was not a member of their church, not a churchgoing man at all.

Paz and Barlow exchanged a look. Barlow said, “Mr. Wallace, was your sister a churchgoing woman?”

“Well, we was both raised in the church. My momma’s a amen-corner lady, you know? But, you know, you get older, sometimes you tend to drift away. I went. Dee, she didn’t always make it.”

“This was from when she started going with Mr. Youghans?”

“Well, yeah, but she been kicking back at it for some years now. Then she got pregnant, you know, and like, that set Momma off on her, and she didn’t like coming around. I got to be like one of those UN guys going back and forth.”

“Uh-huh. Did you have any idea that your sister or her boyfriend was involved in another kind of religion?”

Wallace knotted his brows. “What you mean, like Catholic?”

“No, sir, I mean like a cult.”

A startled expression crossed Wallace’s face. “Like that Cuban shit?”

“Well, anything out of the ordinary, something new she might’ve just got into. Or him.”

The young man thought for a moment, then shook his head. “Not that she ever told me. Of course, since she been going with Julius, we ain’t been that close. But … nah, I kind of doubt it. Dee’s like more of a down-to-earth sort of girl. Was.” A pause here. “There was that fortune-telling thing, if that’s what you mean by something new.”

“And what was that about?”

“Oh, well, she told us, it must’ve been two, three weeks back, she found this fortune-teller dude, and she used to go to him for like, what d’you call ‘em, readings? And anyway, he gave her a number and it hit. That’s how she got that couch and TV and shit. So she was pretty pumped on him for a while.”

“Do you know this man’s name or where we can get ahold of him?”

“Nah, it was some African name. Like Mandela: Mandoobu, Mandola? I can’t remember. She didn’t say much about him. Look, could I just call my mom now? I already told you everything I know, and if I don’t get back to my car there ain’t gonna be nothing but wheels left …”

The two detectives agreed with a glance and sent Raymond Wallace off with a uniform for a drive back to his car, with the cop given private instructions to take his time. Paz drove to Opa-Locka with Barlow beside him, keeping under the speed limit, as Barlow preferred, wishing he could smoke a cigar, something Barlow deplored. Paz imagined he put up with Barlow because the man was a superb detective and because Barlow’s tolerance of Paz gave Paz a certain standing in a department that by and large disliked him. Kissing Barlow’s ass (if that’s what this was) obviated the necessity of bestowing such kissing elsewhere.

The interview with Mrs. Wallace went as these things always did. The Wallaces had imagined that by staying straight, and getting married, and remaining so, and going to church, and pursuing a respectable and honorable life in the military, and moving at last to a reasonably stable lower-middle-class community they could avoid the current Kindermord of the black people, but no. Paz sat in his cool and watched Barlow handle the hysterics. Mrs. Wallace was a hefty woman and took some handling. Peace restored, calls made, neighbor ladies flocking inward, in a ritual of comfort lamentably too well oiled, the two cops got to ask some questions. They learned that Deandra had left home after an argument, had used her survivor’s benefits to pay for the apartment in “that awful neighborhood,” had started to take courses in beauty school. The detectives learned that beauty school had not been the summit of the Wallaces’ dreams for their girl, but kids today … what could you do? Mrs. Wallace had never been in her daughter’s apartment, and she confirmed her son’s story of their estrangement over her affair with Julius Youghans. Julius Youghans was high on Mrs. Wallace’s list of suspects.

“Did he ever threaten your daughter, Mrs. Wallace?” Paz asked.

“He didn’t want her baby, that was for sure,” said the woman. “Julius, he just wanted the one thing.”

By this time, Mrs. Wallace was surrounded by neighbor ladies fanning her with palm fans and paper church fans, and comforting her with the homilies of their desperate, bone-hard religion. After some routine questions confirming the whereabouts of her and her son on the previous night, the detectives left their cards and departed.

Driving back south, Paz ventured, “You starting to like Youghans?”

“Could you do that to a woman you been with? You saw the baby. Could you do that to your own flesh and blood?”

“If I was drunk, or zonked behind angel dust or crank, and if she just told me the baby wasn’t mine? And I had a knife handy? Yeah, I could. Anybody could. It explains how the killer got into the apartment; the vic let him in. And the missing picture fits there, too. It was Julius’s picture up there, and he snatched it off the wall when he left.”

“That wasn’t the only thing he took out of there,” said Barlow pointedly.

“There’s that, yeah, but if we assume he’s crazed …”

“And your crazed jealous killer takes the time to drug his lady friend before he slits her open? And to do what looks to me like a neat little operation on that baby?” He looked at Paz sideways, out of the long white eyes. “You’re about to fall in love, you’re not careful, son.”

That was the first rule of Barlow. Don’t fall in love with a suspect until you know all the other girls.

“Okay, point taken,” said Paz, not at all offended. He had no problem admitting that Barlow had more experience than he did, was at present a better detective. After a brief silence, Barlow said, “I’ll be real interested in what the doc says about those cuts.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I seen some hogs butchered, and deer, and calves, and done it myself a time or two. I seen it done by people knew what they were doing and by people didn’t have an idea in the world how to go about it, and you can tell. What I mean to say, the man that did that, what we saw up there in that apartment, knew what he was

doing. He done it before.”

This last remark hung in the air like a smear of greasy smoke.

“I don’t want to hear that, Cletis.”

“No, and I don’t particularly care to say it, neither, but there it is. The hearing ear and the seeing eye, the Lord hath made both of them, Proverbs 20:14. We got to follow the ear and the eye wheresoever they may lead.”

“Cletis, all I’m saying, can’t we just hope it’s a regular domestic? Because if it’s a serial, a loony, well, it’s going to tie us up forever and have the politicians on our necks and the guy is probably in Pensacola anyway …” Paz gave up. He was conscious of the faint blips in his communication, little subvocal hiccups where, had he been speaking to a regular person, he would have inserted the verbal lubricants fucking, hell, goddamn. He also sensed that Barlow knew this and was enjoying it, to the extent that Barlow could ever be said to enjoy something. Barlow said, low-voiced, almost to himself, “Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean? No one.”

There seemed to Paz no good comeback to this, and the two men drove the rest of the way to their station in silence. There they found that Julius Youghans had a modest sheet on him, some drunk driving and two counts of receiving stolen property. Paz was ready to go out and pick him up for a conversation, but Barlow said, “He’ll keep. If he ain’t run yet, he’ll set. I want to go see the autopsy.”

This was fine with Paz. Barlow had taken the call and was, by rule, the primary detective on the investigation. They’ll probably eliminate suicide right off, he thought, but kept the thought to himself. After Barlow retired he was going to get a partner with a sense of humor.

“You want me there?” Paz could live without autopsies.

“No, no point the two of us going up to Jackson. Why don’t you find out what that nut thing is, and I’ll meet you back here around five and we’ll both of us go see Mr. Youghans.”

Also fine. Paz went back to his car and took I-95, going south this time. He lit one of the unbanded maduro seconds he bought in bundles of fifty from a guy on Coral Way. Paz had been smoking cigars since he was fourteen, and was amused by the recently renewed fashionableness of the vice among downtown big shots. You were not supposed to smoke in police vehicles, which Paz thought was another indication of the end of civilization. Man smoked; it was what made him man, and distinguished him from the beasts.

Night of the Jaguar jp-3

Night of the Jaguar jp-3 The Return: A Novel

The Return: A Novel Tropic of Night jp-1

Tropic of Night jp-1 Valley of Bones

Valley of Bones The Forgery of Venus

The Forgery of Venus The Good Son

The Good Son Valley of Bones jp-2

Valley of Bones jp-2 Night of the Jaguar

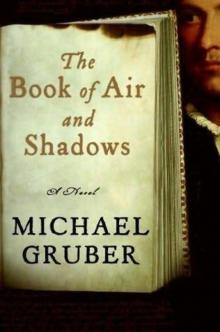

Night of the Jaguar The Book of Air and Shadows

The Book of Air and Shadows