- Home

- Michael Gruber

Tropic of Night jp-1

Tropic of Night jp-1 Read online

Tropic of Night

( Jimmy Paz - 1 )

Michael Gruber

Michael Gruber

Tropic of Night

ONE

Looking at the sleeping child, I watch myself looking at the sleeping child, placing the dyad in a cultural context, classifying the feelings I am feeling even as I feel them. This is partly the result of my training as an anthropologist and ethnographer and partly a product of wonder that I can still experience feelings other than terror. It has been a while. I assess these feelings as appropriate for female, white, American, Anglo-Saxon ethnicity, Roman Catholic (lapsed), early-twenty-first c., socioeconomic status one, working below SES.

Socioeconomic status. Having these feelings. Motherhood. Lay your sleeping head, my love, human on my faithless arm, as Auden says. Maladie de l’anthropologie, Marcel used to call it, a personalized version of Mannheim’s paradox: the ethnographer observes the informant, at the same time observes herself observing the informant, because she, the ethnographer, is part of a culture too. Then at the same time observing herself observing herself as a member of her culture observing the informant, since the goal is complete scientific objectivity, stripping away all cultural artifacts including the one called “scientific objectivity,” and then what do you have? Meaning itself slips from your grasp like an eyelash floating in a cup of tea. Hence the paradox. Geertz found a theoretical solution as far as fieldwork goes, but in the heart’s core? Not so easy.

It is not all that interesting to watch a child sleep, although people do it all the time. Parents do, and perhaps also Mr. Auden, at least once. I am not, however, this child’s mother. I am this child’s mother’s murderess.

The child: female, ethnicity unknown, nationality unknown, presumed American. SES probably five: rock bottom. Four years of age, though she looks younger. In Africa there were kids of eight who looked five, because of malnutrition. Plenty of food around, but the kids didn’t get any. The old folks hogged all the high protein, as was their right. A cultural difference, there. Her skin is the palest red-brown, like bisque pottery. Her hair is black, thick, and quite straight, but dry and friable. She is still thin, her spine a string of staring knobs, her knees bulging out beyond the bones they articulate. I think her mother was starving her to death, although usually if they’re going to starve them they do it in infancy. The bruises are gone now, but the scars remain, thin cross-hatchings on the backs of her thighs and buttocks. I expect that they were made by a wire coat hanger, an example of what Levi-Strauss called bricolage: a cultural artifact used in a new and creative way. I fear brain damage, too, although so far there are no frank signs of this. She has not spoken yet, but the other day I heard her crooning to herself, in well-shaped notes. It was the first two bars of “Maple Leaf Rag,” which is what the local ice-cream truck plays when it comes to the park. I thought that was a good sign.

My own knees are rather like hers, for I am an anorexic. My condition doesn’t result from a neurotic defect in body image, like those pathetic young girls exhibited on the talk shows. I got sick in Africa and lost forty pounds and subsequently I’ve eaten little, for I court invisibility. This is a strategic error, I realize: to become really invisible in America, a woman must become very fat. I tried that for a while and failed; everything came up, and I worried about scarring of the esophagus. So I starve, and try to fatten the child.

In my longings, I wish to be mist, or the ripple of wind on the water, or a bird. Not a gull, a class I feel has been aesthetically overrated, no; but a little bird, a sparrow of the type God watches fall, or a swallow, like the kind we saw in Africa. We had a houseboat on the Niger, above Bamako, in Mali. From its deck we would watch them come from their nests on the soft banks and fill the sky over the river in a pattern of flitting silhouettes in the ocher dusk, and in their hundreds and dozens of hundreds they would hunt the flying insects and dip to drink sips from the oily brown surface. I would watch them for their hour, and would pray that they contained the souls of women dead in childbirth, as the Fang people are said to believe.

She blows a tiny bubble in her sleep, so babyish an action that my heart flows over with love and for an instant I am rejoined to my true self, not watching from outside, like an anthropologist, or a fugitive, which is another thing I am, and after that instant the fear flows back again like batter in a bowl from which a finger has been withdrawn. Affection, attachment, weakness, destruction, not allowed, not for me. Or remorse. I killed a human being. Did I mean to? Hard to say, it went down so quickly. Hold a knife to my throat and I’d tell the truth: the child was doomed with her, she’s better off with me, I’m glad the woman’s dead, God rest her soul, and I’ll answer for it in heaven along with all the other stuff. Worse stuff.

Naturally, the little girl doesn’t resemble me in the least, which is a problem, for people watch us and wonder who did she fuck to get that one? No, actually, that’s unfair: most people don’t see us at all, both of us are good at fading into the foliage, going gray in the shadows. We go out in the dusk, before the quick fall of the tropical night, or, as on the weekend just passing, very early. Tomorrow I will have to find a place to put her while I work. I have only a little sick time left and I need the money. She has been with me ten days. Her name is Luz.

I took her to the beach yesterday, to Matheson Hammock, very early in the day, and we paddled in the blood-warm shallows of Biscayne Bay, she holding my hand, stepping cautiously. We found a yogurt container and she filled it with various beach wrack?a cocolobo seed, a fiddler’s claw, a tiny horseshoe crab?while I scanned the perimeter like a marine on point. As we waded, a car came up and rolled down the drive behind the beach. It’s secluded there under the mangroves and is a favorite place for smooching and for dealing drugs. When we heard the car door open, she ran to me. Unlike me, she’s afraid of strangers. I’m only afraid of people I know.

After the beach we went to the Kmart in South Miami. I bought her a pail and shovel, some cheap shorts and Tshirts, underwear and sneakers and socks. I let her choose a lunch box and some books. She chose a Bert and Ernie lunch box and a Bert and Ernie book and a Golden Book about birds. She’s had some exposure to TV, clearly, although I do not own one and she seems content with that. For myself I bought a pair of polyester slacks the color of rust or of some diseased internal organ, and a sleeveless red top printed to look like patchwork and decorated with small cute animals on alternate patches. Although not quite the ugliest outfit in the store, it was at least a contender. Also, it was a size too large, and it was on sale.

The checkout lady smiled at Luz, who hid her face against my thigh.

“She’s shy,” said the checkout lady.

“Yes,” I said, and reminded myself not to come through the line again when this person is on duty. Reject connection is my rule, although I now see that this will no longer be quite as feasible as it once was, when I was alone. Luz is attractive, and people will notice her and strike up conversations, and it’s more memorable to coldly reject than to smear bland conversational margarine about. “Yes, you’re shy, aren’t you?” I say with a coo to the girl, and to the woman, as I pay (cash, naturally), “She’s always been shy. I hope she’ll grow out of it.”

“Oh, they usually do, especially a pretty little thing like that.”

Already she has forgotten us, her eyes moving automatically to the next customer.

We walked out of the frosty emporium to the sun-sizzled parking lot and into my car, a Buick Regal, in blue, from 1978. Its body is pretty well rusted out, the rocker panels having achieved the texture of autumn leaves. Both passenger windows are cracked, and the trunk doesn’t lock. A yellow chenille bedspread serves as the front seat cover. On the other hand, it has

the V-8 in there and the engine, the drive train, and all the running gear are as tuned and as slick-running as it is possible for a twenty-year-old machine to be. It is the kind of car you want for pulling bank jobs and getting away: fast, reliable, anonymous. I did all the car work myself. My dad taught me. He collected and restored cars. Still does, I suppose, although I haven’t been in contact with home of late. I tell myself it’s for their protection.

We got into the car, and rolled out of the lot onto U.S. 1. We live in Coconut Grove, a part of the city of Miami. It’s a nice place to live, if one is actually living, and if not, people there tend to leave you alone. It retains some of the louche and freewheeling atmosphere it was famous for some years ago, but if you talk to anyone who was here in the sixties and seventies, they will assure you that it’s ruined. I once spoke with an old woman who said that the best time was before the war. She meant the second world one. Nobody had a dime, she said, but we knew we were living in paradise. In those days, huge flying boats used to come down from New York and land on Biscayne Bay right at Coconut Grove and the wealthy passengers would have dinner ashore. The place is still called Dinner Key and the great hangars still exist. The Grove is certainly ruined, as will be any place in America that has cheap funky housing and artists living in it and some community energy going on. The rich people want to be around that, having drained it out of their own lives in the course of making a pile, and so they move in and build great big houses and shopping malls, and create the quaint, where once there was real.

Of course, the Grove is not as ruined as it might have been because black people live there, in their own mini-ghetto west of Grand and south of McDonald. In America, if you are willing to tolerate the sight of a black face on the street you can get a good deal on your housing and the developers will not bother you until they have chased all of them away.

We live on Hibiscus Street off Grand, in a neighborhood that clearly is scheduled for gentrification, being on the good (or white) side of Grand, but that repels the money boys still because half the houses are owned by black people who have not yet been taxed out. They are Bahamians and Dominicans and African-Americans. The rest of the inhabitants are white people who don’t mind this or positively love it. Myself, I’m as indifferent to race as it is possible to be: that is, I am somewhat racist, like everyone else in my nation. There is no escape. On our street we have several run-down cinder-block apartment houses, painted pink or aqua, so there is transience and a moderate amount of crime. This is fine with me; the transience is cloaking; I have nothing to steal; I can defend my body against anything but a gun.

Our apartment is above a garage, painted brick red with white trim, like a barn. The front room has two tiny windows looking out on a dust-and-shell driveway, and the back room, where I sleep, has a big sliding glass window from which you can see a tangled hedge of cream hibiscus and pink oleander. The window is so large and the room is so small that when the window is open it is almost like sleeping outside, or in an African house.

In my bedroom is a thin mattress, resting on a door, supported by six screw-on legs, each of which stands in a can half full of water. This is an old fieldworker trick to keep the roaches from chewing the dead skin off you while you sleep. The child sleeps there now. I have my string hammock, slung from hooks in the wall, low, so I can watch her and touch her if I wish. The rest of the furniture is junk from the garage or collected during walks around the neighborhood: a warped pine bureau with two out of three drawers, a chaise lounge I restrung with thick cotton rope, a pine table, three mismatched wooden straight chairs, a pink fur bean bag, a brick-and-board bookshelf. Over the table is a hanging bulb in a Japanese paper globe. Next to the kitchen is a tiny bathroom, with a stained claw-foot tub with shower and the usual facilities. Its once-white walls are scabrous with mildew. We have no air-conditioning. A fourteen-inch Kmart fan blows garden air over us at night. The one closet is an anal-obsessive’s fantasy of order, although I don’t recall being particularly obsessive when I was living real life. It’s just that I’ve spent a lot of my time in VW vans, and Land Rovers, and tents, and hovels, and boats, and I’m very good at storage and retrieval. Kmart sells a nice line of wire-rack organizers and I’ve bought largely in their closet department. When I moved in here, the walls were pink-orange and the floor was covered with avocado shag. I decided that, if I was going to die here, I didn’t want my last sensory impression to be avocado shag, and so I ripped it up and replaced it with cheap black vinyl tiles and I painted the walls white. The walls are bare. When I was laying the tiles I found a corner missing out of one of the four-by-eight plywood sheets of the floor. I made a plywood hatch for this hole, and tiled over it, and it fits so closely that you have to yank it up with a big glazier’s suction cup. What I have to hide, I hide there.

After Kmart, we drove to the Winn-Dixie, where I now shop. I used to eat so little that it wasn’t worth going to the supermarket and I’d just pick up something, yogurt, or chicken, or soup, at a convenience store. That’s where I found the child, in a mini-mart on the east side of Dixie Highway, down south someplace. I forget what I was doing there, but sometimes, at night, in the summer, the sticky heat and the insect noises remind me of Africa, and I have to ride, to hear the mechanical sounds of driving and smell exhaust, the dear stench of my homeland, and feel the wind of speed on my face. At around two in the morning, I went in to get a cold drink and she was there, filthy, in ragged shorts and a torn pink T-shirt and flip-flops, standing in the aisle. She was shaking.

I said to her, “Are you okay? Are you lost?” She didn’t answer. The woman behind the counter was fussing with the frozen slush machine and had her back turned. I walked away to the drink console.

As I reached for a cup, I heard the first slap and looked around. The mother was there, a large tan woman in her twenties, with her hair in curlers under a green print scarf. She was wearing Bermudas and a tube top that barely covered her bobbling breasts. Whoever she had once been, that person was gone, or in deep hiding, and only a demon stared out of the red-rimmed eyes. The child was holding her hand to her ear, and her face was screwed up like a piece of crumpled tinfoil, but she made no sound.

“What did I tell you? Huh?” said the mother. She held a forty-ounce bottle of malt liquor in one hand. With the other she beat the child, big roundhouse blows that knocked the little girl against a frozen-food lowboy hard enough to bounce.

“What did I tell you, you stupid little bitch? Huh? (Slap.) Huh? Did I tell you not to move? (Slap.) I told you not to move, didn’t I? (Slap.) Wait’ll I get you back home, I’ll fix you good. (Slap.) What the fuck you lookin’ at, bitch?”

This last was directed at me. I pulled my eyes away from the scene and left. I stood with my cold hands pressed to the warm hood of my car and took deep breaths. I thought of what the Olo say, of something that happens between an adult and a particular child, part of their weird rearing practices. But that was in Africa, I told myself. I tried hard to shut down the feeling.

I heard the door of the mini-mart slam open and the mother and her child emerged and walked toward the corner of the little building. There was a dark alley there that led to the next street, where I supposed they lived. It was a typical South Dade highway-side neighborhood, small concrete-block stucco houses, a few low apartment buildings, still looking bare and exposed after Hurricane Andrew. The woman was holding her forty-ounce beer bottles slung over her wrist in their plastic carrier bag, and was dragging the child along by the arm, twisting it cruelly, muttering to herself. The child was trying to relieve the pain by turning herself toward the woman and in the process, just as they passed into the alley, the girl got in the way of the woman’s legs and she tripped. They both went down on the rough limestone gravel. The woman saved her bottles and let the girl fall on her back. Then the mother yelled out a curse and got to her feet and kicked the girl in the side. The girl curled up into fetal position and covered her head with her pipe-cleaner arms, whereupon I ran u

p to them yelling, “Stop that!”

The woman turned and glowered at me. “Get the fuck outa here, bitch! Mind your own fuckin’ business.” I moved closer and I could smell the sweat and the alcohol boiling off her.

“Please. Let her alone,” I said, and she took two staggering steps toward me and launched a clumsy overhand blow at my head.

I caught her arm in hiki-taoshi and brought it around behind her back, ude-hineri, and bent her over double and marched her a few yards away and pressed her face into the gravel. I had not done any serious aikido in years but it turned out to be something you don’t forget how to do, like riding a bike. I said, “Stay here, please, I’m going to see if your little girl is all right.” And I rose and walked back to where the child lay unmoving.

I suppose I was on autopilot by then, in some kind of trance from the African thing that was happening, which is not all that uncommon among the Olo, but still unexpected in a South Dade mini-mart, and that is the only excuse for what I did next. The mother did not stay put but came after me in drunken rage, cursing, and I whipped around and caught her left wrist and spun her out in jodan-aigamae-nagewaza. In aikido dojos, subjects of this throw go easily into a forward roll to their right and bounce up smiling; but now, in the dark alley, the woman’s 160 or so pounds were lofted at speed through the night with the force of her own charge, and her head struck the corner of the Dumpster parked there with a dreadful, final sound.

Thick blood poured from an angular dent in her head, and a dark stain was spreading along the center seam of her Bermudas. She was as still as the loaded trash bags that surrounded her. I did not check to see if she was as dead as she appeared, but went to the child and took her hand. She came willingly with me and we got in my car and rolled. As I drove, I looked back into the sickly light of the mini-mart window and saw that the proprietor was still messing with the disassembled pieces of her slush machine. She had never looked at me. I had touched nothing in the store. I asked the child what her name was, but she didn’t answer. By the time we passed Dadeland, she was asleep.

Night of the Jaguar jp-3

Night of the Jaguar jp-3 The Return: A Novel

The Return: A Novel Tropic of Night jp-1

Tropic of Night jp-1 Valley of Bones

Valley of Bones The Forgery of Venus

The Forgery of Venus The Good Son

The Good Son Valley of Bones jp-2

Valley of Bones jp-2 Night of the Jaguar

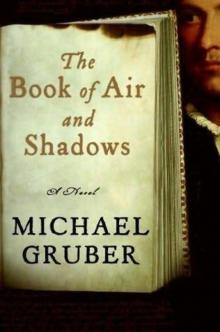

Night of the Jaguar The Book of Air and Shadows

The Book of Air and Shadows