- Home

- Michael Gruber

The Return: A Novel

The Return: A Novel Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For E.W.N.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Also by Michael Gruber

About the Author

Copyright

Sobre el pecho de México

tablas escritas por el sol

escalera de los siglos

terraza espiral del viento

baila la desenterrada

jadeo sed rabia

pelea de ciegos bajo el mediodía

rabia sed jadeo

se golpean con piedras

los ciegos se golpean

se rompen los hombres

las piedras se rompen

adentro hay un agua que bebemos

agua que amarga

agua que alarga más le sed

¿Dónde está el agua otra?

OCTAVIO PAZ

from Vuelta (Return)

On the chest of Mexico

tablets written by the sun

stairway of the centuries

spiral terraces of wind

the disinterred dances

anger panting thirst

the blind fighting beneath the sun of noon

thirst panting anger

beating each other with stones

the blind beat each other

the men are crushing

the stones are crushing

within there is a water we drink

bitter water

water that increases thirst

Where is the other water?

1

Mexico.

This was Marder’s first thought when the doctor explained what the shadow on the screen meant, what the tests implied. Mexico meant unfinished business, put off for years, nearly forgotten, until this unexpected deadline: now or never. That was the decent part; the cowardly part was the terror of explanation, of seeing the faces of his friends and family wear that look, the one that said, You’re dying and I’m not and as much as I care for you I can’t treat you like a real person anymore. He could see this very look in the doctor’s face now, presaging all the others to come. Gergen was a good guy, a fine GP; Marder had been seeing him for years, the annual checkup. Something of a joke this, for Marder was hale as a bear, arteries like the bore of a Mossberg 12-gauge, all the numbers in the right zones, remarkable for a man in his fifties. They had a good relationship; if not quite pals, they’d always joked through the exams, the same jokes. Marder always said, “Tell me you love me first,” as the doctor slipped the greased, rubbered finger up toward the perfectly normal prostate.

And other humorous repartee before and during: current events, sports, but mainly books. Marder was a book editor of some reputation—he’d been editor in chief of a major house before turning freelance some years back. Gergen fancied himself a literary fellow, and Marder usually remembered to bring along the latest thing he’d worked on, a history, a biography; today it had been one explaining the origins of the financial crisis. That was his editorial specialty, doorstops dense as nougat that explained our terrifying new world.

Gergen was explaining Marder’s own new world now. The thing was deep in the brain, immune from surgical intervention, immune even from the clever methods by which a tube could be passed up the arterial pathways to fix the deadly little bubble. When Gergen finished, Marder asked the usual question and got the usual answer: impossible to tell. It could stop growing, which occasionally happened, for reasons unknown; the most likely scenario was leakage, stroking out, the hideous decline, stretched out over months or years; or it could just pop, in which case, curtains, and the next world. Marder had believed in the next world all his life, more or less, and did not entirely dread the journey, but lingering—in paralysis, helplessness, idiocy—filled him with horror.

They shook hands solemnly when Marder was dressed and ready to leave. Gergen said he was sorry, and Marder could tell he meant it but also that he was glad to see him go. Doctors are irritated by those beyond help; Marder knew the feeling—he’d worked with any number of authors who couldn’t write and wouldn’t learn. Irritating: death, like lack of talent, an embarrassment to be avoided.

* * *

Marder left the doctor’s office and walked toward Union Square, through the thronged streets, weaving in the practiced New Yorker’s way through all the people who were going to outlive him, who would be in their lives after he was not. He found that this knowledge did not depress him. His step was light; he cast his eye almost benevolently at the passing faces, so many of them bearing the grim mask of the New Yorker, guarded, intent on the next deal or destination. The world seemed sharper than it had when he entered the office just a few hours ago, as if someone had wiped clean his smudged glasses. He had almost reached the park when it struck him that the last time he had felt this preternatural clarity was years ago, when he was a soldier in Vietnam, in the night forests along the Laotian border. This, too, was strange: Marder almost never recollected that war.

Ordinarily he would have taken the subway home, but now he walked. The day was fair, sunny, cool, a nice September afternoon in the city; nature did not mourn for him, no pathetic fallacy on offer for Marder. As he walked, his mind bubbled with plans; it was free with the liberty of the void. This is the first day of the rest of your life, as the happiness advice books always said, but since there was also a chance that it was the last day, the silly phrase took on a more interesting, more cosmic overtone, what the sages meant about living in the Now.

Marder was a deliberate man, a careful thinker, a detail guy, but now his mind seemed to be running with unusual speed, concentrated with the prospect of dying, at some date to be determined. So bemused, he nearly stepped into the path of a cab at Houston Street. Yes, that would solve it: the black bubble of suicide floated across his mind, quickly punctured. Quite aside from the religious objections, Marder knew he couldn’t do that to his children, not two parents checking out that way, but now came the thought that placing himself in a situation where he was likely to be killed was not at all the same thing, especially if by so doing he could accomplish his purpose down in Mexico. His mind steadied, plans started to jell. He didn’t know if he could do it, but it seemed right to die trying.

* * *

At Prince Street he passed a group of street musicians, South American Indians by the look of them, in woven ponchos and felt hats—a pair of flutes, a drummer, a woman with a rattling gourd who sang in a high and nasal voice. Marder spoke fluent, almost accentless Mexican Spanish, but her lyric was difficult to follow, something about a dove, something about the ruin of love. When the song ended, he dropped a twenty in her hat among the singles and coins, was rewarded by a brilliant flash of white teeth, in the shining obsidian eyes a look of amazed gratitude. She blessed him in the

name of God, in Spanish; he returned the blessing in the same language and walked on.

Marder’s generosity here was not connected to his recent news; he often gave ridiculous sums away, although always privately. Proust, he’d heard once, habitually tipped 100 percent, and Marder occasionally did the same. Although born into modest circumstances, Marder was rich, secretly rich, through a stroke of luck so absurd that Marder had never accepted it as his due, making him different from nearly every other rich person of his acquaintance: wealth without feelings of entitlement was something of a rarity, in his experience. That he still worked at all, and in a profession not noted for excess remuneration, was a bit of uncharacteristic deviousness, a cover story. Only his lawyer and his accountant knew how much he was worth. His children and a number of other beneficiaries would be extremely surprised at probate.

Continuing south on Broadway, he passed a massive industrial building with an ornate cast-iron front. The ground floor of this structure boasted a strip of elegant eateries and boutiques; the rest of it contained luxury condos. During his boyhood, however, it had been a printing plant, where his father had worked for thirty years as a Linotype operator. It always gave Marder a tiny pang when he happened to pass by. Maybe it was mere nostalgia, but he thought there was something wrong about a city that had become largely a dwelling of the very rich and the people who serviced their needs. He missed the city of his boyhood, then the greatest port, the largest manufacturing entrepôt on earth. He recalled it as exciting and comprehensible in a way that the current city was not—a place that now shipped only digits, that made nothing but money. He thought he wouldn’t miss this aspect of the city in the time he had left.

The Tribeca loft he lived in was currently worth a bit over a million, but this was easily explained: he’d bought it back in the early eighties with an insurance payoff from his father’s death. “Lucky stiff!” was the usual comment. Real estate bonanzas were hardly unusual in the city, and no one thought it remarkable. It was even true, but not nearly as remarkable as the larger story.

Having reached this loft, Marder went to the area he used as his office, sat at his desk, and began to disassemble his life. He had a book in process, and this he passed off on a subcontract basis to another freelancer he knew, who had a pregnant wife and a pair of school-aged kids. Marder stifled the man’s effusions of gratitude; that was the easy part. Then he called the author and broke his heart, pleading unspecified health issues as an excuse, assuring him that the work would be competently done and that, to make up for dropping the project, he would reduce the contracted completion payment. He would have to make up this fee to the substitute editor (a wonderful man, several books on the List, you’ll love him, and so forth), but that would not be a problem.

Third call: Bernie Nathan, the accountant, who asked, when he heard what Marder wanted, whether he was in some kind of trouble. No, he was not, and could Bernie have the cash on hand this afternoon? Fourth call: Hal Danielson, the lawyer. A few little changes to the will. A similar question, similarly answered: no, not in trouble at all.

Fifth call: H. G. Ornstein answered on the first ring. Ornstein’s business, which was running a tiny left-wing journal, was clearly not pressing. After the pleasantries and the usual damning of the condition into which our once-great nation had fallen, Marder asked, “So, Ornstein, you still living with your mother?”

Yes, and it was driving him crazy; wonderful woman, but not so wonderful living in the same house. Ornstein’s wife had, after many years of noble poverty, despaired of the inevitable victory of the people and filed for divorce. Ornstein, a decent man, had done the decent thing and moved out. Marder did not believe in the ultimate victory of the people either, but he admired grit and selflessness. He’d known the man since college, when Ornstein had also tried his hand at stand-up comedy in the angry lefty mode of Mort Sahl or George Carlin. The man was a dead-on mimic but lacked edge, and had failed at that too.

When Marder told him he needed a friend to look after his loft for an indefinite period, the phone line hissed silence for nearly thirty seconds, then another undesired gush, to which Marder replied, “No, don’t thank me, you’ll be doing me a favor. I’ll drop the keys and paperwork in the mail today. Can you move in Friday? Great.”

* * *

Now Marder’s finger brought up the contact list on his cell phone but hesitated above the next necessary number. Time for some procrastination. He went to the closet in the loft’s bedroom and pulled out a battered leather gladstone bag of Mexican manufacture. He had not used it in some time, for now he traveled with a black nylon roll-aboard like the rest of humanity, but he thought that this one was the right container for his truncated new life. Into it went lightweight shirts and trousers, the usual underwear and toilet articles, a linen jacket and a leather one, leather sandals, several softly worn bandannas, a real Panama straw hat, the kind you could roll up. He hung his best suit in a garment bag, providing for any formal event or to be buried in. He placed the packed bag at the foot of his bed and then opened a tall, narrow steel safe.

Marder was not exactly a gun nut. He disliked the policies of the National Rifle Association and thought the general availability of powerful semiautomatic weapons in his nation was insane, but, despite that, he liked guns. He admired their malign beauty as he admired tigers and cobras, and he was a wonderfully proficient shot. From his gun safe he brought out a rifle and two pistols, together with all the boxes of ammunition he had on hand. It was irrational, he knew, but he did not want his survivors to have to dispose of them. Besides, it was always convenient to be armed on road voyages through the regions of Mexico where he intended to travel. He asked himself why he cared, since the thing in his head was more or less in charge of his life. Mr. Thing, as he now decided to call it, had its own agenda. Mr. Thing could discharge him from his life without notice, but in the meantime he would remain Marder, although a Marder who would not be an occasion of pain to the people he cared about.

In furtherance of this goal, he now placed himself at his computer and shopped for a truck, for he did not want to fly commercial, which could be traced. It took him only half an hour to arrange for the purchase of a Ford F-250 fitted with a seven-foot hardwall Northstar camper, model name “Freedom,” which Marder thought pretty amusing under the circumstances. The seller was in Long Island City, and Marder made an appointment to pick it up late that day. Another call to Bernie: courier a check over to the dealership. This time Bernie did not ask questions.

* * *

Marder spun on his chair and looked around the office, reflecting that he’d spent an extraordinary amount of time within these walls. Two of them, the ones in view of his desk, were painted eggshell. Set into one of these was the big industrial-scale window looking out on Worth Street. Behind him, the rear wall of the room and the remaining sidewall were painted bloodred. That had been Chole’s section of the home office. He had his elegant steel-and-rosewood desk, his back-saving leather chair, infinitely adjustable with little wheels and levers. Her desk was the antique rolltop with pigeonholes he’d bought her for their fifth (or wooden) anniversary. She had used a wooden office chair she’d brought in from the sidewalk in the days of their poverty, its cushion upholstered in bright serape cloth. Above her desk, a broad section of the wall was covered in thick cork panels, on which she’d stuck family photos, posters, found objects, cartoons, newspaper and magazine clippings from the Mexican press. The report of the murder of her father and mother, for example. A photograph of Esteban de Haro d’Ariés, that father, when young and smiling and holding his daughter, aged four, for example.

She’d been doing this for a long while, and the corkboard had become a palimpsest of her life in exile, untouched in the three years since her death. Marder had long since stopped looking at it closely but had a good look at it now. On one side of the cork hung a torero’s shining cape and on the other an enormous crucifix, its corpus gray-skinned, bloody, twisted, agonized, nailed to the

rough wood of the cross with real iron nails. It looked as if it had been sculpted from life, and considering that it had come from Michoacán, it might have been. A lot of strange things happened down there, where she was from.

He removed the newspaper clipping about the murders. It had been torn roughly out of the pages of Panorama del Puerto, the newspaper in Lázaro Cárdenas; on it his wife had written lines from a poem by Octavio Paz on the occasion of the famous massacre of students in 1968. He translated it silently:

Guilt is anger

turned against itself:

if an entire nation is ashamed

it is a lion poised

to leap.

Maddened by grief—an antique concept perhaps, but Marder had seen it played out in this very dwelling, this room. No one had been punished for the murders, just another pair out of the forty thousand or so that the narcoviolencia had claimed. Everyone knew who had done it, and by all reports he was still enjoying his life, buoyed by an ocean of dollars and his apparent impunity. Marder carefully folded the clipping and placed it in a slot of his wallet, as if it were a set of a directions for the operations of a complex mechanism. A trap of some kind—no, an ambush: a lion poised to leap.

Marder had no corkboard. Instead, he had a whiteboard, inscribed in dry marker. It listed book schedules, chapter outlines, things to do. He took a rag and wiped it clean; so much for his life. A transient weakness passed through his body, and he had to sit in his chair for a moment and catch his breath. Then he turned to the file cabinets. His and hers: twin four-drawer wooden models. Hers was empty—the kids had cleared it out after she died. The upper three drawers of his contained his professional life: editorial notes, contracts, and so on, most of them from years ago, before the world turned digital. A good proportion of the paperwork was in Spanish because, for the last ten years or so, Marder’s fluency in the language had led him into the business of arranging Spanish translations of works in English. For many big Latin American media firms, Marder was one of the go-to people in New York. No more, obviously.

Night of the Jaguar jp-3

Night of the Jaguar jp-3 The Return: A Novel

The Return: A Novel Tropic of Night jp-1

Tropic of Night jp-1 Valley of Bones

Valley of Bones The Forgery of Venus

The Forgery of Venus The Good Son

The Good Son Valley of Bones jp-2

Valley of Bones jp-2 Night of the Jaguar

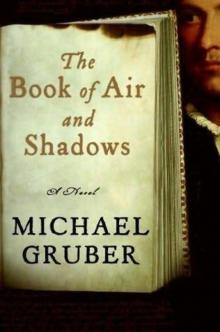

Night of the Jaguar The Book of Air and Shadows

The Book of Air and Shadows